About one in seven people is neurodiverse, according to the BBC. What does this mean? Why is it a good thing? And how should it affect our work as healthcare marketers, particularly as we (rightly) talk more about digital accessibility and inclusion in our work?

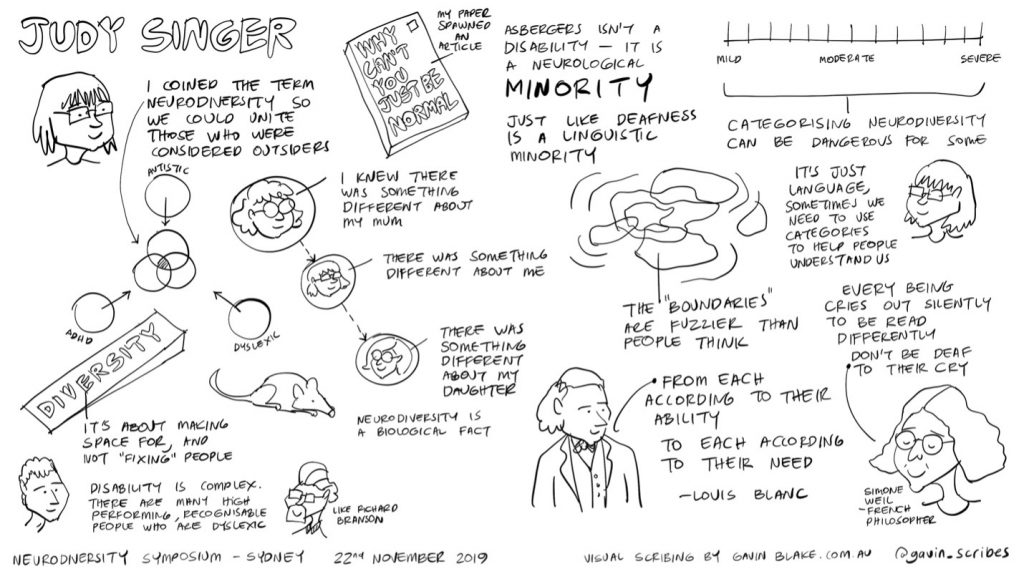

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) affects about 1 in 50 people (adults and children), according to the CDC. But neurodiversity, a broader term, encompasses ASD, as well as ADHD, dyslexia, Tourette syndrome, and other neuro-cognitive variations. The term was coined in 1997 by Judy Singer, an Australian sociologist. The following image illustrates a talk Singer gave on the origins of the term in 2019.

It may be approximately true – if reductive – to say that one feature of neurodiversity is the ways in which a person reacts to the stimuli and information they encounter in the world. They often process some of that differently than a “neurotypical” person would. Similarly, neurodiverse people also sometimes express themselves differently, in language or other behavior than a “neurotypical” person might.

Because of these differences, neurodiverse people have historically been misunderstood, feared, discounted, and, at worst, subjected to horrific violence. They are also more likely, statistically, to face unemployment and barriers to professional success.

The myth of “typical”

But what does “typical” even mean? As an article titled “The Myth of the Normal Brain,” published by the AMA, points out:

“There is no … standard for the human brain. Search as you might, there is no brain that has been pickled in a jar in the basement of the Smithsonian Museum or the National Institute of Health [sic] or elsewhere in the world that represents the standard to which all other human brains must be compared. Given that this is the case, how do we decide whether any individual human brain or mind is abnormal or normal?”

As with so much else in biology and life, the way human brains work is on a spectrum, not a binary.

As author Jenara Nerenberg put it, “Neurodiversity is recognizing the array of human brain makeups as beautiful and natural, rather than pathologizing some.”

Encouraging society to consider, include, and embrace the neurodiverse community better, in all that we do, is powerful and necessary of its own accord, of course. (For instance: did you know that the CDC’s first study of autism in adults was done … only last year?) It is simply the right thing to do, for neurodiverse people and for humanity overall, to adjust outdated, misinformed structures and assumptions: to learn, to understand, and to act, to be more inclusive. But embracing neurodiversity has additional consequences that provide pleasant supplementary benefits to the world.

First, it opens the world to the extensive potential benefit that neurodiverse minds hold.

In a Harvard Business Review article titled “Neurodiversity as a Competitive Advantage,” the authors pointed out that the skills neurodiverse people possess, and hone, are often highly sought after by employers. Organizations increasingly, as they put it, “have reformed their HR processes in order to access neurodiverse talent – and are seeing productivity gains, quality improvement, boosts in innovative capabilities, and increased employee engagement.” The article provides a how-to with seven elements that companies can institute to do the same.

A recent pair of letters in The Lancet titled “Autistic Doctors: Overlooked Assets to Medicine” and “Lived Experience Commentary” makes similar points: that “employers, managers, and colleagues can no longer afford to overlook the potential of autistic doctors purely because these doctors do not conform to existing systems favouring the neurotypical clinician.”

And, as J.P. Morgan simply put, in a quote for the International Board of Credentialing and Continuing Education Standards, “Our (more) neurodiverse teams are 50-90% more productive.”

Second, it offers the opportunity to make the world better – certainly, for those who need the changes most, but, in addition, for everyone else as well.

Software company Ultra Testing has a workforce which is 70% on the autism spectrum. CEO Rajesh Anandan notes that their policies, such as allowing workers to select how many hours they work, isn’t a question of “creating ‘accommodations’ for particular groups. We’re redesigning the system so it’s better for all groups.”

The “curb cut effect” is the term for – as Anandan puts it – “accommodations” that, once instituted, turn out to help everyone, not just the specific group of people they were expected to benefit. Universal design does, in fact, benefit universally. For instance, as the name “curb cut effect” suggests, sidewalk ramps don’t just help people in wheelchairs: they help people with strollers, suitcases, carts, bicycles, etc. Closed captioning, which only dates back to the late 1970s, doesn’t just help people who are deaf or hard of hearing, but everyone. You’ve probably been in a noisy public space and read captions – and, if you’re like me, you read as many social media videos as you listen to.

What can healthcare marketers do?

We must consider that the patients and HCPs – the ones we’re here to help – include many neurodiverse people. Are we including that consideration in our work? Here are a few ways:

- Consider, and point out, ways that a patient can retain familiar structure, even in the face of the challenges of diagnosis or treatment.

- Be mindful to use direct, concrete language, and avoid metaphor, irony, or other types of communication that could be confusing, particularly when discussing important facets of care.

- Mention neurodiversity and its concerns as a matter of course, helping to normalize the conversation and the discussion of it.

- Consider how a person managing things like sensory overwhelm might be impeded when interacting with your content, and brainstorm ways to work through that with different, and better, options.

- Vet support, advocacy, and research organizations thoroughly before collaborating with, or referencing, their work, because the understanding of many conditions changes over time, and some organizations – Autism Speaks is one example – are not seen as reflecting the current views of many people in the community.

The far-ranging variety of neurodiversity offers potential to be maximized, not problems to be weeded through. As noted advocate Dr. Temple Grandin put it, “The world needs all kinds of minds.”

Creating content and tools that can be accessed by people with disabilities is vital to healthcare marketers. To learn more about creating digitally accessible content, read our recent POV on this important topic, along with this recent blog post.